Climate Change at a Glance

Two slides, one story of a warming planet.

This short project was part of my MSc module Climate Change and Environmental Hazards. The task: explain the causes and global impacts of climate change in just two slides.

When I started, I approached it like any science assignment, with facts and data. But I soon realized that these two slides tell a much larger story. They show how human activity is changing the balance of the planet, and how those changes ripple through every system that supports life.

We already understand what’s happening and why.

The question now is what we choose to do with that knowledge — and what it will take to act on it.

Human activity now dominates Earth’s energy balance, which means that it has become powerful enough to alter the balance of the planet – a planet we share with millions of other species. That doesn’t mean nature has stopped acting. It means that our influence has become comparable to geological forces like volcanism or orbital shifts.

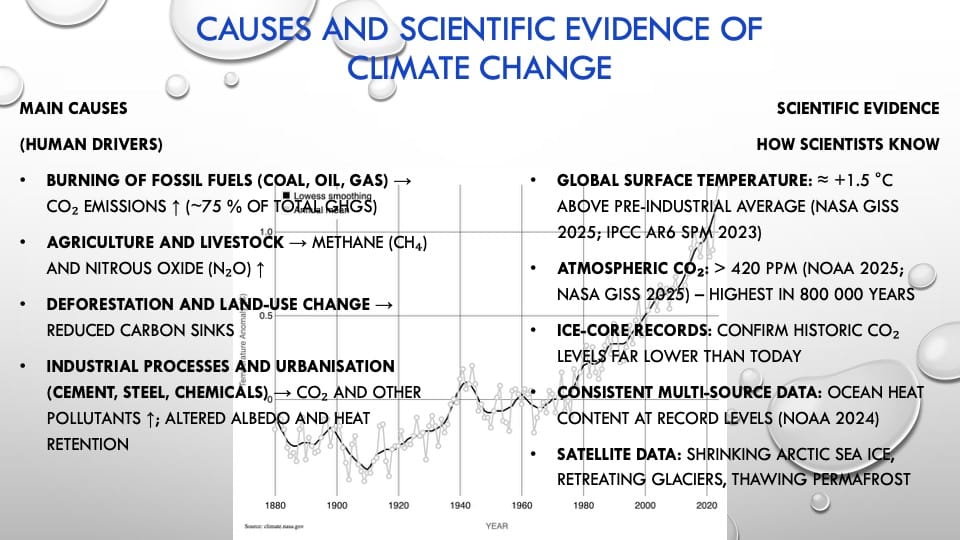

The mechanism is simple: we burn fossil fuels, releasing CO₂ and other greenhouse gases that trap heat in the atmosphere.

Multiple independent datasets from NASA, NOAA, and the IPCC all confirm the same pattern. Global temperatures have risen by about 1.47°C since the late 19th century, and the ten most recent years are the warmest on record.

The signals and evidence come from every direction: from air bubbles trapped in ice, from satellites watching the planet's surface, from ocean buoys and long-term weather stations that have quietly measured the same steady rise.

Together, they tell one consistent story: the world is warming because of us.

Human activities emit greenhouse gases → greenhouse gases trap heat → the planet warms.

It is that simple, and that consequential.

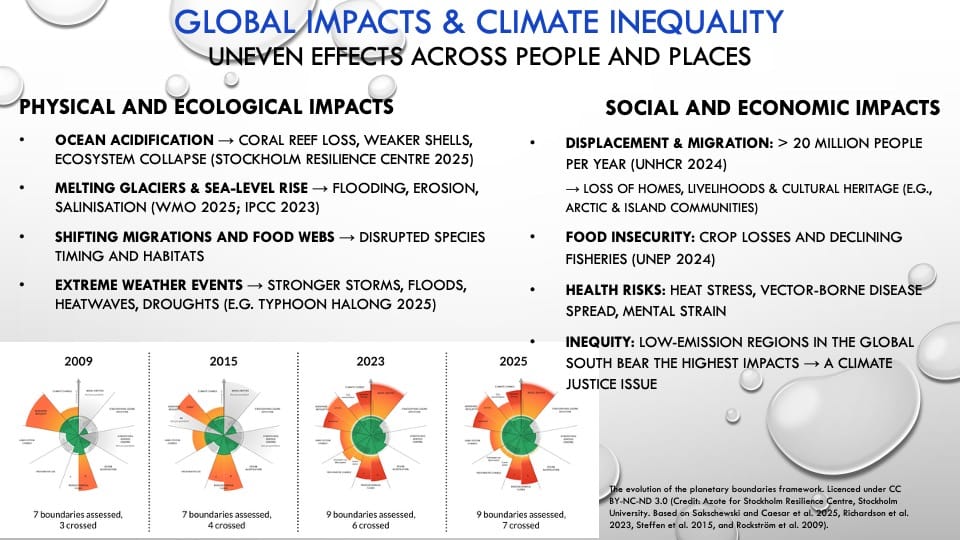

The same forces that heat the planet also destabilize it.

Warming amplifies droughts, floods, and storms, but the burden is not shared equally. Those least responsible for emissions – Indigenous communities, small island nations, rural farmers – are often the ones who pay the highest price.

In policy terms this is called Loss and Damage.

In human terms it means lost homes, broken traditions, and shifting seasons that no longer align with memory.

Climate change is not only an environmental issue but a justice issue.

The science shows the pattern. The people living at its edges show the cost.

Conclusion

When I look at these two slides now, they no longer feel like coursework. They read like a short story about the world we're living in now. Urgent, real, and shared.

We already know what drives climate change, and we know what to do to slow it down: phase out fossil fuels, protect and restore ecosystems, and change how we produce and consume energy.

The question is why knowing is not enough.

Part of the answer lies in how humans deal with crisis. We protect ourselves from what feels too big or painful to face. We fragment the story, reduce it to statistics or headlines, or turn away out of fatigue, much like we do with grief.

And while personal stories are crucial, they need to be tied back to the whole system. Without that context, empathy has nowhere to go.

We’ve also grown used to streaming climate change – tracking data, scrolling through disasters, sharing outrage, competing over whose loss counts most – instead of translating knowledge into collective action. People need clear guidance on what meaningful action looks like, and how daily choices connect to planetary health.

The danger isn’t that people don’t care; it’s that we’ve been cut off from the understanding that caring actually changes outcomes.

Climate change is not a single story. It is all our stories, told through air, water, soil, and time.

Maybe this is where science communication has to evolve: from transferring knowledge to restoring relationship, from describing change to helping people recognize themselves inside it.

As humans, we crave order and certainty. We want to make sense of complexity, to break it into pieces we can manage. But when the picture gets too big or too uncertain, we start to shut down. Somewhere in all that, we forgot how to live in relationship — with the Earth, with each other, with what sustains us.

At some point, someone looked at the ground and said, “I’ve got this great idea,” and began to pull ancient sunlight out of stone. That idea built the modern world and the illusion that extraction could go on forever. But we can’t keep letting corporations tell that single story of endless growth.

Understanding our place in the whole means seeing through that illusion and remembering that we’re participants in a shared living system, not spectators or outside manipulators.

Because once we stop watching the story unfold and start living inside it, change stops being someone else’s task and becomes our shared responsibility.

References

•IPCC (2023) Sixth Assessment Report: Synthesis Report Summary for Policymakers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (Accessed: 24 October 2025).

•NASA (2025) Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Available at: https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/ (Accessed: 24 October 2025).

•NOAA (2025) Climate. Available at: https://www.noaa.gov/climate (Accessed: 24 October 2025).

•United Nations Environment Programme (2024) Emissions Gap Report 2024: No more hot air … please! With a massive gap between rhetoric and reality, countries draft new climate commitments. Available at: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/46404 (Accessed: 24 October 2025)

•Stockholm Resilience Centre (2025) Planetary Boundaries Framework.

Available at: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html (Accessed: 24 October 2025).