Climate Models, Energy Balance, and the Math of Inevitability

A short attempt to rescue climate modeling from both mystique and dismissal (and to name why it hurts to understand it)

This week I’ve been reading a 2016 paper by Thomas Anderson, Ed Hawkins, and Phil Jones that traces the evolution of climate models from early, hand-calculated energy budgets to today’s Earth system models. Their story doesn’t begin with supercomputers or satellite networks, but with a Swedish chemist named Svante Arrhenius writing calculations by hand in 1896.

For me, Arrhenius wasn’t a climate thinker at first. I first came across his name in Chemistry 101, attached to acids and bases: acids increase hydrogen ions, bases increase hydroxide ions, and together they neutralize to form water. Only later did I realize that the same scientist who helped define chemical neutrality also helped define something else: planetary imbalance.

He showed, more than a century ago, that increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would trap heat and warm the Earth. Not as an opinion. As a consequence.

And what Anderson, Hawkins, and Jones make clear is that climate modeling isn’t a jump from primitive ideas to modern wisdom, but a continuous lineage. Today’s Earth system models didn’t replace those early insights; they are their descendants.

Somewhere between the first handwritten energy budgets and today’s global simulations, a weighty truth emerges:

Climate models are the mathematics of inevitability.

Not in the sense of a fixed future, but in the sense of constraints. When the constraints of a physical system change, the system responds in ways that are predictable, even if the consequences unfold unevenly. Raise greenhouse gases and more heat is retained. Retain more heat and ice melts. Melt ice and the planet reflects less sunlight. Oceans warm, seas rise, ecosystems shift, and heat increases further.

You don’t have to “believe” any of this. Physical systems respond regardless of what we believe.

And everything else in this story is downstream of one question:

Where does the energy go?

Once you start following that question upstream, models stop feeling like opinions and start feeling like accounting.

And if you’ve ever thought “models are just guesses,” the surprise is this: the core of them is the same radiative physics Arrhenius was working with by hand; we’re just now running it inside a coupled, living planet.

The physics behind inevitability

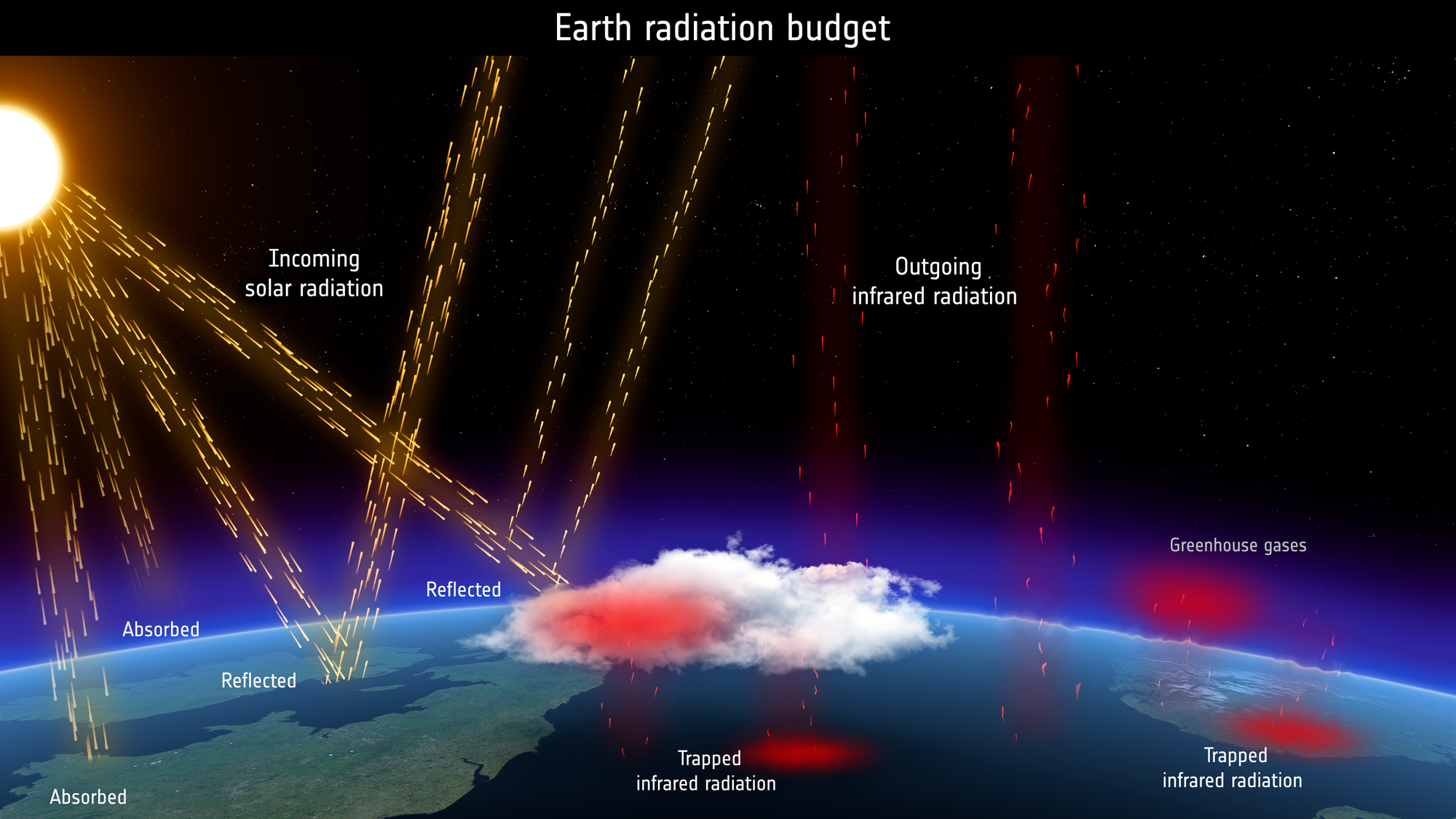

Earth is an energy-balance system in the way that matters for climate: energy arrives from the Sun and must either leave back to space as heat, or remain within the Earth system. The balance between those flows is what determines planetary temperature.

Energy doesn't disappear; it moves. Climate change is what it looks like when we reroute the pathways.

When humans burn fossil carbon that was locked underground, we move carbon into the atmosphere in the form of heat-trapping gases. We rearrange matter that took millions of years to settle into long equilibrium, and we do it fast.

It’s tempting to think that because carbon is natural, its rearrangement must be harmless. But carbon behaves very differently depending on where it sits, how concentrated it is, and how quickly it’s moved.

Once CO₂ accumulates in the atmosphere, radiative transfer takes over.

Radiative transfer is the physics of energy moving through air: sunlight arrives, Earth re-emits heat, and greenhouse gases absorb and re-emit part of that heat, slowing its escape to space.

It’s not a minor technical detail. It’s the core mechanism linking atmospheric chemistry to temperature.

If you change the composition of the atmosphere, the temperature must change.

Physics doesn’t negotiate.

And once warming begins, a chain of feedbacks follows. This is where inevitability stops being abstract. Feedbacks are where a small imbalance starts to compound:

- Ice–albedo feedback: ice melts, darker surfaces absorb more heat.

- Water vapor feedback: warmer air holds more water vapor, strengthening warming.

- Carbon cycle feedbacks: warming soils and ecosystems can release stored carbon.

- Circulation shifts: oceans and atmosphere reorganize heat and moisture patterns.

Once you see climate as an energy-balance problem, you’re forced to confront a humbling fact: even with that clarity, the system remains deeply complex over long timescales.

Deep time: why ice ages are still the core riddle

One of the most honest and humbling parts of Anderson et al.’s paper is the way it widens the lens to deep time. They return to the ice ages, because that’s where Arrhenius began, and they say, essentially: even today we don’t have a single, complete answer for what drove temperature changes large enough to produce glacial cycles, because the full explanation lives in radiative balance across interacting influences.

That “we don’t have a full answer” isn't weakness. It’s what intellectual honesty looks like inside a coupled system.

The lineage matters:

Joseph Fourier recognized Earth should be colder if it simply radiated heat to space. He inferred that the atmosphere must impede the escape of “dark heat” (infrared), even though he did not identify which gases did it.

John Tyndall later showed experimentally that CO₂ and water vapor absorb infrared radiation.

Milanković cycles (orbital variations) help explain slow shifts in incoming solar distribution, but orbital forcing alone can’t explain the magnitude of glacial swings without feedbacks involving greenhouse gases, ice, and oceans.

What deep time does is keep you honest. Radiative balance sits at the center, and everything else layers onto it: ice, oceans, greenhouse gases, circulation.

That’s why radiative balance remains the organizing principle across timescales.

Energy budgets and “balance” (the part that confuses almost everyone)

When people hear that “Earth is out of balance,” it can sound like moral language, like a value judgment, as if there is one perfect climate state we are meant to return to. In climate science, it means something far simpler: bookkeeping. On average, incoming energy and outgoing energy no longer match.

Earth has occupied many balanced states. Ice ages were balanced, just colder. Warm interglacials were balanced, just warmer. Balance doesn't mean “unchanging.” It means not accumulating energy over time.

So why do scientists say the system is out of balance now? Because Earth is currently gaining energy.

The simplest accounting looks like this:

Net energy = incoming sunlight − outgoing heat to space

If that number is positive, the system must warm until outgoing heat increases enough to restore balance.

Here is the part that breaks intuition.

Greenhouse gases do not add heat to the Earth system.

They change how long heat stays, and the altitude and temperature at which it escapes.

As greenhouse gases increase, infrared radiation emitted by Earth’s surface is absorbed by GHGs and re-emitted multiple times before reaching space. The effective altitude from which Earth loses heat therefore moves higher in the atmosphere. Higher altitude means lower pressure and colder air, and colder air emits less infrared radiation per second.

The result is subtle but decisive: for the same surface temperature, less energy escapes to space. Incoming solar energy remains largely unchanged, while outgoing energy is reduced.

Physics resolves this imbalance in only one way.

The planet warms until it emits enough infrared radiation to restore balance.

The adjustment mechanism is warming itself — which is why the thing that “fixes” the energy imbalance is also what damages ecosystems, infrastructure, and life. That is thermodynamics colliding with biology.

Even if we stopped adding CO₂ tomorrow, the altered radiative structure would not instantly disappear. Greenhouse gases don't vanish when emissions stop, and the heat already stored in oceans and land doesn't disappear on political timescales.

Reducing emissions stops the imbalance from worsening. It doesn't rewind the system to where it "started."

That is why baseline arguments so often get stuck. There is no cosmic baseline written into nature. Scientists use reference periods as measuring sticks, often the pre-industrial period (before large-scale fossil fuel combustion), and often the Holocene because it’s the stability window human civilizations were built inside.

These reference periods let us ask: how far, and how fast, are we pushing the system away from the conditions our ecosystems, food systems, water cycles, and infrastructure implicitly assumed?

The key word is rate

Earth can handle high CO₂ in deep time. It has, many times. What it has not experienced is such a rapid alteration of the atmosphere’s radiative behavior: the rapid narrowing of the "exits" through which heat leaves the system.

Energy keeps flowing in, but it stays longer. Heat accumulates in oceans, ice, and land faster than slow-moving systems can adjust. The imbalance is not explosive; it is cumulative.

What matters is not simply how much energy is retained, but how quickly it accumulates relative to how slowly the system can respond and re-equilibrate.

This is how inevitability takes shape: through delay, retention, and momentum.

Slow systems don't fail loudly.

They fail quietly, by falling out of sync.

And this is the hinge that brings us to everything that follows, into scale collapse, into misread signals, into the limits of lived experience, and ultimately into why we need models at all.

Scale collapse: when comfort is mistaken for stability

One of the hardest things about climate change is not denial, but scale collapse.

What happens is this: People experience local, short-term comfort, interpret it as system-level reassurance, and broadcast it as proof that "everything is fine."

Warm winter days can feel genuinely pleasant. Sun on skin in December can register as comfort, novelty, even freedom. But climate change doesn't primarily violate our senses. It violates our timescales.

Personal experience operates at the scale of days and emotions. Climate operates at the scale of decades and energy flows. Social media captures surfaces. Climate models track what is happening underneath: ocean heat uptake, soil moisture shifts, altered circulation, delayed ice response.

You can enjoy a warm winter afternoon and still be living inside a system that is quietly accumulating stress. Both can be true at the same time.

We keep trying to measure a planetary system with feelings. But nervous systems aren’t designed to register slow energy imbalance, which is precisely why models exist.

Three layers of value in climate models

Reading Anderson et al. (2016), three layers of value come into focus:

Conceptual clarity

Arrhenius was conceptually right in 1896: more CO₂ leads to a warmer planet.

Physical realism

Mid-20th-century models added vertical structure, circulation, oceans, and feedbacks. Manabe and Wetherald (1967) showed how radiation and convection shape atmospheric temperature, a foundational step toward modern climate modeling.

Marginal refinement

Modern ESMs add carbon-cycle feedbacks, aerosols, sea-ice physics, vegetation dynamics, and chemistry. These refinements improve detail and confidence, but they do not reverse the outcome.

The most useful sophistication is what clarifies behavior, not what merely adds detail.

What Earth system models are intended to do

Earth system models simulate the climate system as an interconnected whole. They link atmosphere, ocean, ice, land, vegetation, and chemistry. They represent feedbacks between components and allow exploration of different futures under different emissions choices.

They’re physics engines. They won’t tell you if it rains on a specific Tuesday in 2092. They test what follows from physical law under different emissions pathways. They show how the system behaves under these pathways.

And they resolve spatial patterns, not just global averages, which is essential for understanding where impacts concentrate and for planning adaptation.

How climate models have changed over time (and what each stage can and cannot do)

| Model approach | What it did | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy budget (Arrhenius, 1896) | Hand-calculated planetary heat balance, CO₂ warming estimate | Conceptual clarity, right direction | No realistic geography, limited feedbacks |

| Empirical detection (Callendar, 1938) | Combined observations with rising CO₂ | Linked emissions to observed warming | Sparse data, limited dynamics |

| 1D radiative-convective models | Added vertical atmospheric structure and radiation physics | Connects gases to temperature profiles | No 3D circulation, crude clouds |

| Atmospheric GCMs | 3D circulation patterns | Spatial patterns and variability | Early models weakly coupled to oceans |

| Coupled ocean-atmosphere models | Added ocean heat uptake and variability | Stronger long-term projections | Limited biogeochemistry |

| Earth system models (today) | Adds carbon cycle, chemistry, vegetation, aerosols | Scenario testing across coupled systems | Uncertain processes, high computing cost |

Adapted from Anderson, Hawkins and Jones (2016)

"Likely", uncertainty, and future risk

Anderson et al. discuss ensembles and probability language. In IPCC-calibrated terms, exceeding 2°C becomes likely under higher-emissions pathways, where “likely” is defined as a 66–100% probability range. This calibration matters: it allows institutions, countries, and disciplines to coordinate around shared language.

But calibrated language also holds a risk. It can subtly shift attention from physical processes to verbal categories, inviting debate over wording instead of engagement with the system itself. Probabilities help us compare futures; they don’t soften the physical consequences of whichever future we land in.

Ensembles aren’t one forecast. They are distributions of outcomes produced across multiple simulations. The spread is how uncertainty is carried in a disciplined way: how much, how fast, and where patterns unfold. Models can generate distributions and explore tails.

The hardest uncertainties aren’t the greenhouse effect itself, but processes like clouds, aerosols, and regional circulation and precipitation, which is why local impacts have wider ranges than global temperature.

Since 2016, scenario framing has evolved, but across scenarios, the consistent direction is clear: higher emissions produce more warming, shifting precipitation patterns, intensifying extremes, and increasing long-term sea-level rise — while rapid emissions reductions reduce those risks. The “core physics plus feedbacks” storyline remains intact.

And there’s a public gap here that matters:

Public assessments often foreground what can be said with high confidence in probability language, words like “likely” that are meant to be legible across institutions, countries, and cultures. That’s useful, but it also creates a trap: the planet doesn’t operate on confidence thresholds, and planning can’t either.

Planning has to stress-test the tails, not because they’re predictions, but because high-impact, low-likelihood futures still govern what happens to infrastructure, food systems, insurance markets, and political stability.

That’s why “plausible worst-case” scenario work exists: UK risk work led by Arnell explicitly frames these as high-impact, low-likelihood stress tests. It’s a practical question, not a rhetorical one: what happens if we land in the tail anyway?

This distinction matters: prediction versus risk, probability versus consequence. It shows up wherever complex systems meet human decision-making.

The real question isn’t if models are perfect. It’s about what we're willing to plan for based on what they already show. Without models, we would be blind to accumulation until impacts became unavoidable.

The mushroom metaphor

Mushrooms appear after rain: sudden fruiting bodies emerging from soil and fallen leaves. They look random and patchy. But the real architecture lies underground, vast mycorrhizal networks shaping where moisture, nutrients, and energy flow.

Climate models work the same way.

The visible outputs (graphs, maps, projections) are the fruit bodies.

The hidden machinery (radiative transfer, carbon cycles, feedbacks) is the network below.

What rises to the surface may surprise us, but nothing violates the deeper rules.

Climate models don’t predict the future by looking forward; they reveal the future by turning inward, tracing how energy moves through a system, the way moisture moves through soil and mycelium. The mushrooms at the surface look surprising, but nothing they do contradicts what’s happening below.

And this metaphor is not just poetic.

Fungal fruiting is sensitive to temperature and moisture. Kauserud and colleagues documented systematic shifts in mushroom phenology across Europe as climate conditions changed. Mushrooms don’t predict the future. They respond to the present. They reflect changes in soil moisture, temperature, and seasonal timing. They’re signals from the underground.

What matters isn’t if a mushroom appears here or there, or if a regional projection is off by 12%.

What matters is the structure underneath:

- energy balance

- rate of forcing

- feedback-driven cascades

- the difference between “likely” outcomes and plausible tails

- the fact that lived experience is not a climate diagnostic tool

This is where humans struggle.

Humans want certainty before acting.

Complex systems only deliver certainty after momentum is built, because of delay, inertia, and irreversibility.

That mismatch is the trap.

Climate models exist because humans can't feel slow accumulation. Nervous systems evolved to detect predators, not energy imbalance. Models are not comfort tools. They are early-warning instruments, a form of long-range sensing.

Once you see that, the question isn’t “do you trust the models?” anymore.

The only honest question left is this:

What do you do with what they already make clear, while choice still exists?

Physics will restore balance either way. Adjustment will happen. What remains is a fork: societies reduce forcing upstream—deliberately, collectively—or adjustment is imposed downstream, on landscapes, species, and futures that never agreed to the terms.

Who speaks for forests, rivers, wolves, soils, and future generations in decisions made today, and how do we build that voice into systems that currently reward only the present?

The throughline, in one sentence

Energy sets the rules; balance tells us if the system is accumulating heat; rate tells us how violently it will reorganize; feedbacks explain why small shifts compound; models quantify the consequences; lived experience misreads the signal; and risk is what arrives when we don’t plan for what physics already implies.

Energy → balance → rate → feedbacks → modeling → lived misinterpretation → future risk

10 things that shift when you follow the energy upstream:

1) Climate isn’t a debate. It’s accounting.

Most people think climate arguments are about opinions, politics, or “trusting scientists.” Aha: It's energy bookkeeping.

2) “Natural" isn’t the point. Placement + speed is. (Carbon underground ≠ carbon in the air.)

Aha: “Everything is natural stuff” is a category error.

3) Energy balance isn't moral language.

Aha: ice ages were “balanced.” Balance doesn’t mean “healthy” or “ideal”; it means “not drifting.”

4) There’s no “perfect baseline.”

Aha: reference periods are measuring sticks, not commandments.

5) Rate is the real stressor.

Earth has seen high CO₂, yes, but not this fast with this infrastructure + biosphere. Aha: not just how much change, but how fast.

6) Feedbacks are how small becomes self-reinforcing.

Aha: warming isn’t linear; it can compound, accelerate, and cascade.

7) Models aren’t crystal balls; they’re physics engines.

Aha: models don’t need to predict a day to reveal a trajectory.

8) Uncertainty ≠ ignorance. Uncertainty is a distribution.

Aha: ensembles are the disciplined way to hold uncertainty: how much/where/when, not if.

9) Risk isn’t only the most likely outcome.

Aha: planning has to stress-test tails. Even low-likelihood outcomes matter when impacts are huge.

10) Surface signals are mushrooms. The rules are underground.

Aha: outputs vary; the hidden network is the physics. The structure persists.

References

Anderson, T.R., Hawkins, E. and Jones, P.D. (2016) CO₂, the greenhouse effect and global warming: from the pioneering work of Arrhenius and Callendar to today’s Earth system models. Endeavour, 40(3), pp. 178–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endeavour.2016.07.002

Arrhenius, S. (1896) On the influence of carbonic acid in the air upon the temperature of the ground. Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 41(251), pp. 237–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786449608620846

Manabe, S. and Wetherald, R.T. (1967) Thermal equilibrium of the atmosphere with a given distribution of relative humidity. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 24(3), pp. 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1967)024

IPCC (2023) AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (Accessed: December 27, 2025).

Arnell, N.W., Hawkins, E., Shepherd, T.G., Haigh, I.D., Harvey, B.J., Wilcox, L.J. et al. (2025) High-impact low-likelihood climate scenarios for risk assessment in the UK. Earth’s Future, 13, e2025EF006946. https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EF006946

Kauserud, H., Heegaard, E., Büntgen, U., Halvorsen, R., Egli, S., Senn-Irlet, B., Krisai-Greilhuber, I., Dämon, W., Sparks, T., Nordén, J., Høiland, K., Kirk, P., Semenov, M., Boddy, L. and Stenseth, N.C. (2012) Warming-induced shift in European mushroom fruiting phenology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(36), pp. 14488–14493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1200789109