Holding the River

On Steelhead, Ritual, and Reckoning

I didn’t grow up fishing or living by the river, yet spending time on and near Idaho’s Clearwater River taught me something about reverence and reckoning. This essay isn’t about optimism or pessimism; it’s about presence, about staying with beauty and loss at once, and learning what belonging might mean in a time of collapse.

Each fall on Idaho’s Clearwater River, not far below the dam in Orofino, a few drift boats still slide into the current. They wait for the steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) to come home, ocean-going rainbow trout that travel thousands of miles and climb eight dams to return to the gravel beds of their birth. It should be a celebration, a living covenant between water and flesh. But it feels more like a vigil.

I’m not an angler by tradition. I came to these rivers as a learner, a watcher, sometimes rowing, sometimes just breathing in the fog and diesel. What I saw there reshaped how I think about belonging and about how easy it is to love the wild while helping it disappear. But let me explain.

Steelhead are not salmon, though they share the same story. Both hatch in cold inland waters, drift downstream as smolts, and spend years in the Pacific before returning to spawn. But while most salmon die after one journey, steelhead can survive, heal, and swim back to sea again. They are persistence embodied (Kurlansky, 2020). In that way they mirror us — yet persistence alone is not resilience.

Every part of a river is alive. Beneath its surface, dissolved oxygen, temperature, and flow decide who can survive. Steelhead rely on cold, well-oxygenated water to move upstream, and when reservoirs slow the current, that chemistry shifts. Warmer water holds less oxygen. Algae blooms where it shouldn’t. Pathogens thrive. The invisible physics of flow — the same currents that sculpt stones and carry silt — also carry genes, nutrients, and the memory of migration. A river isn’t a backdrop; it’s an organ in Earth’s body.

The steelhead that reach Idaho now are the survivors of a system we built for convenience: concrete walls, hatcheries, temperature spikes, barges. What we call a run is really a slow emergency. And what we call fishing has become a ritual of yearning inside an unraveling world.

Men still go out there with oars and patience. They rise before dawn, pay for their licenses, follow the regulations, fuel the same management machine that trapped the rivers in bureaucracy. They're not villains; most love these rivers fiercely. For many, it is ritual around food, a way of knowing where sustenance comes from, of refusing to live off plastic and packaging maybe. I understand that. There’s an intimacy in it too — the way their boats and bodies move with the current, the way a hand resting on the oar or in the water becomes part of the river’s rhythm. In that closeness lies belonging, or at least its memory.

But I also see the shadow beneath it. We’re all participants now in a system that sells us back fragments of the wild we helped destroy.

Once, on this same river system, the Nez Perce (Nimiipúu) people tended the salmon nations with ceremony and restraint. Their First Foods rituals placed water and fish at the center of moral law: take only when the run is strong, thank the giver, return the first catch to ensure the cycle continues. Their modern descendants still work to restore what was lost; they are breaching levees, replanting riparian shade, reintroducing wild genes instead of mass-produced ones through their Fisheries Department (Nez Perce Tribe, n.d.). They are scientists and stewards both, practicing what their elders always knew: belonging is reciprocal.

You can’t engineer belonging.

You can’t farm the wild.

Yet that is exactly what the modern world tries to do. Hatcheries flood the rivers with uniform fish, masking collapse. Agencies count success in numbers, not in continuity.

Even in Germany, where salmon vanished from the Rhine and its tributaries more than a century ago, there are “Lachsprogramme” — the VAKI fish counter in Leverkusen and the Sieg restoration project — earnest and hopeful, but often more guilt than vision. We breed the symbol but not the system that could sustain it.

Since the early 1990s, groups like the SAV Bayer Leverkusen e.V. and the Wupperverband with the Bergischer Fischereiverein have run small hatcheries — like the one at the Auermühlenwehr on the Dhünn — releasing young salmon and counting “returners” through VAKI monitoring stations. These local projects now operate under the broader Wanderfischprogramm NRW coordinated by LANUK and the Stiftung Wasserlauf NRW, which have reintroduced Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) to rivers like the Sieg, Dhünn, and Wupper.

The water is cleaner and migration routes are improving, and sometimes a salmon even returns to the Dhünn or the Sieg. People marvel when a salmon returns to the Dhünn, as if seeing a ghost (I did too, watching the men release smolts into the Dhünn). Could it be that the memory is gone? Most of those fish still originate from hatcheries, not wild spawning. It's progress, but not restoration (Stiftung Wasserlauf NRW & LANUK, n.d.).

Progress without wildness feels the same everywhere.

Sometimes it feels as if we’re paddling happily across the surface of a river while, deep underneath, the wildness that once held everything together has slipped away. These rituals we cling to — fishing, drifting, feeling connected for a moment — were born in a world that no longer exists. It’s like watching your child play with a polar bear stuffed animal while the last real bears cling to melting ice. The snowfall still looks beautiful, yet every year it falls thinner, weaker, more uncertain. I’m not a pessimist. I see wonder in small things every day. But I refuse to numb myself just to bear it all.

This isn’t despair. It’s the veil lifting. It’s the moment you realize that belonging rituals only work when the world you belong to is intact.

The Truman Show moment

It’s the moment where you suddenly understand:

“Wait… this thing we’re doing to ‘belong’ is actually only possible inside an artificial system that’s collapsing.”

It’s like waking up inside The Truman Show and realizing the backdrop is painted. The river we fish today is not the river that brought about the tradition. The wildness that made the practice sacred is the very thing that is now missing. What once connected us has quietly become obsolete.

It’s not so much about slow systems as it is about a psychological break, a sudden shift into seeing reality clearly.

In the Salish Sea, the southern resident orcas (aka SRKW) (Orcinus orca) are starving. They depend on Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), their largest prey, and as the runs decline, the whales travel farther and find less to eat (NOAA Fisheries, 2024). Across the Columbia–Snake basin, organisations and coalitions like the Columbia Snake River Campaign are working to remove the four lower Snake River dams and replace their services so that salmon, orcas and communities can recover together (Columbia Snake River Campaign, n.d.). The web is collapsing: salmon feed the orcas; salmon feed the forests; salmon feed the land that feeds us all. And none of this collapses in isolation. The strength of a river begins far downstream. Even the estuaries and coastal wetlands — those blue carbon ecosystems where smolts learn the sea — are fraying. Break the coast, and the mountains feel it.

Still, people romanticize the drift boat, the mountain man, the quiet hero with oars and patience. Men cling to these images because they remember a time when strength meant providing, when skill equaled worth. But the truth is that the old “manly things” — conquest, harvest, domination dressed up as ruggedness — are no longer what the world needs.

The rivers don’t need more mastery; they need gentleness.

The mountains don’t need more heroes; they need healers.

That doesn’t mean men must abandon the wild. It means they must evolve with it.

Row the same rivers, but row for restoration.

Cast lines for data, not trophies. Tag, record, release.

Turn the drift boat into a classroom, a citizen-science vessel, a sanctuary for memory.

Keep the rituals, but change the intent, from taking to tending.

A truly nature-positive culture would do exactly that. It would measure success not in production but in regeneration, in how quickly a watershed recovers its self-governing rhythm. It would see infrastructure not as concrete and code but as the living tissue that holds ecosystems, people, and memory together. Yet the systems we have built — dams, markets, bureaucracies, even the language of “sustainability” — have become an infrastructure of distraction. They shape our minds to accept partial healing as enough. They keep us busy managing symptoms while the cause runs deeper. Reverence becomes a luxury instead of a compass.

To stay present with these rivers is to practice coexistence in its truest form — not only between species, but between our own conflicting feelings. Love and loss. Grief and gratitude. Hope and despair. They all live together here, like eddies around a river rock. This is what it means to be an entangled activist: to keep showing up, to bear witness, to let beauty break your heart without turning away (Lawson, 2021).

I love the wild.

And I refuse to numb myself.

And I refuse to pretend.

And I refuse to be quiet.

Because what truly constitutes harm today is not only the killing of a fish. It's the refusal to see context, the belief that personal restraint can replace collective repair. Harm is pretending we can keep playing at wilderness while the wilderness disappears beneath us.

The greatest force shaping collapse is the collective trance of disconnection:

the belief that we are separate from nature,

separate from each other,

separate from consequences,

separate from tomorrow.

People don’t destroy what they feel intimately connected to.

People destroy what they are numb to.

This global numbness, this sleepwalking, is the deepest (d)river. Too many people walk through the world like zombies.

Not evil.

Not uncaring.

Just dissociated.

This isn’t about blaming individuals. It’s about naming the systems that taught us to dominate what we should have been in relationship with. You cannot rebuild a collapsed ecosystem with the same worldview that destroyed it.

And what keeps me awake at night is knowing that extinction is not theoretical. If the southern resident orcas disappear, a whole culture of the sea vanishes with them — a lineage, a language, a memory older than our nations. Nothing has ever broken my heart more than knowing we could lose a species in real time while people sleepwalk past the warning signs.

Having to "artificially" return species is never ever going to replace all that. "Restoring" salmon, like we're doing in Germany, is not restoring memory, lineages, genetic resilience, ecosystems. It's simply playing zookeeper. We should never strive to get to play zookeeper. We should strive to reconnect to our truest, wildest, original selves.

When will it be okay to fish again for sport?

When the rivers run free enough that a returning steelhead is no longer a miracle but a certainty.

When salmon spawn in the Sieg and the Elbe and the Columbia without human scaffolding.

When our descendants inherit abundance, not apology.

Until then, every cast is a question, every catch a confession.

We row and float these rivers not as conquerors, not even as providers, but as witnesses holding vigil for a future in which people and rivers, fish and memory, might finally learn to belong again.

Further Reading and Context

Kurlansky, M. (2020) Salmon: A Fish, the Earth, and the History of Their Common Fate. New York: Patagonia Books.

Lawson, A. (2021) The Entangled Activist: Learning to Recognise the Master’s Tools. Axminster: Triarchy Press.

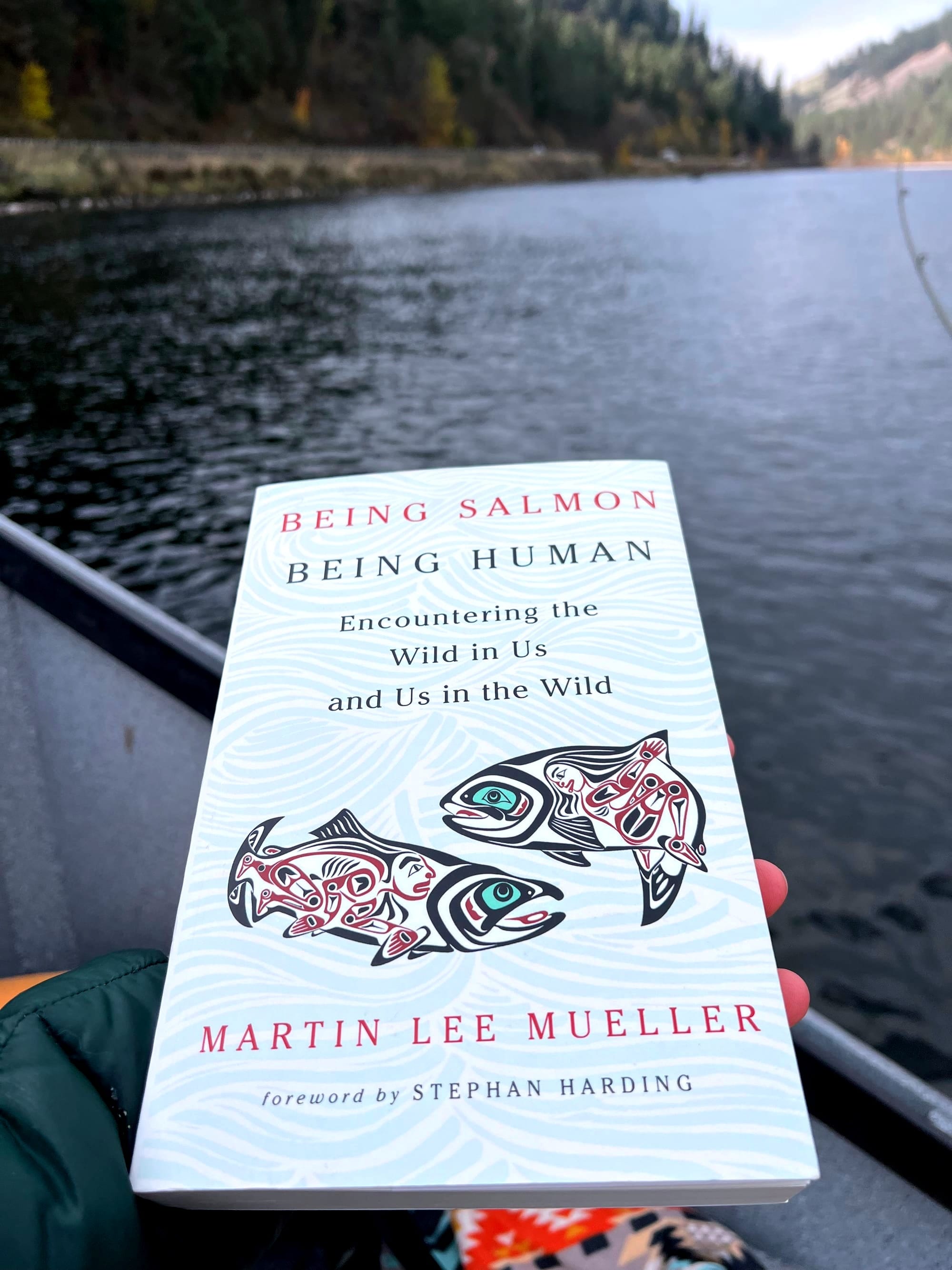

Müller, M. L. (2019) Being Salmon, Being Human: Encountering the Wild in Us and Us in the Wild. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Nez Perce Tribe (n.d.) Fisheries Department. Available at: https://www.nptfisheries.org/home (Accessed: 26 October 2025).

SAV Bayer Leverkusen e.V. Lachsprogramm Leverkusen / Auermühle an der Dhünn Bruthaus. Available at: https://sav-lev.de/projekte/wanderfisch-programm (Accessed: 26 October 2025).

Stiftung Wasserlauf NRW & Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Klima Nordrhein-Westfalen (LANUK) Wanderfischprogramm NRW – Wiederansiedlungsprojekt Lachs. Available at: https://www.wasserlauf-nrw.de (Accessed: 26 October 2025).

Author’s Note

Written from Oberbergisches Land, remembering the Clearwater River in Idaho.

Photograph below: reading Being Salmon Being Human on the river while steelhead were still returning.