Storm Lines and Story Lines: Learning Relational Resilience from Haida Gwaii

A reflection on Indigenous governance, COP30, relational knowledge, and teaching school kids in the Bergisches Land

Resilience comes from relationship.

This week I kept circling back to three moments that, strangely, spoke to each other, even though they happened in completely different contexts.

• Haida Gwaii preparing for storm surge and coastal change

• Indigenous Peoples in Brazil protesting at COP30, demanding protection of their territories

• A group of school kids in the Bergisches Land sharing their ideas about justice and fairness

What connects these scenes isn't politics. It’s the idea of resilience.

Resilience, at its simplest, is the ability of a system to absorb and bounce back from disturbance or shock and keep living — not unchanged, but still itself.

The more I read, listen, travel, learn, and teach, the more I realize that real resilience never comes from extraction, fortification, or competition.

It comes from relationship, and more specifically, from relational exchange and reciprocity.

This post is my attempt to follow that thread, and maybe you’ll see what I mean as you read.

1. Haida Gwaii: A coastline responding through relationship

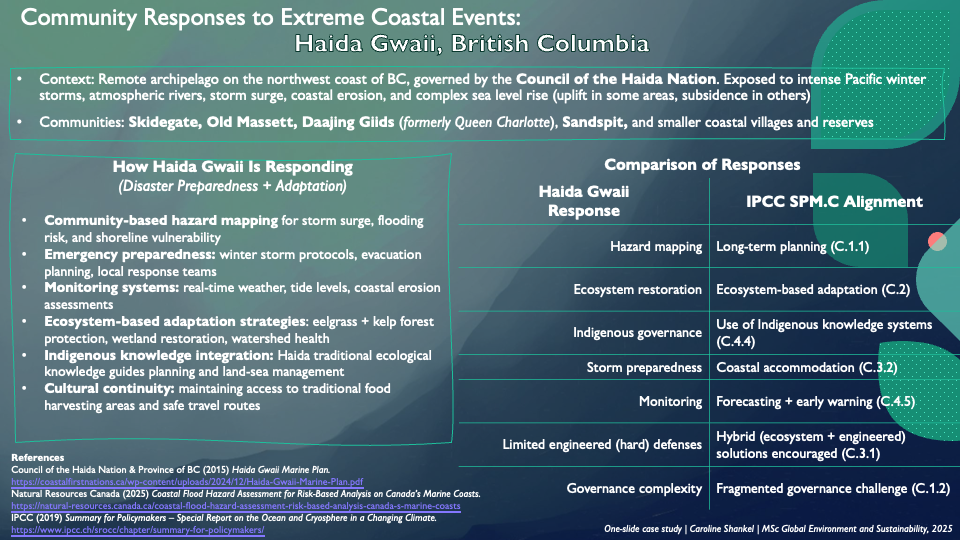

As part of my MSc module, I created a one-slide case study on how Haida Gwaii is responding to sea level rise and extreme coastal events. What stood out most was not the urgency of risk, but the steadiness of their approach.

Their responses emphasize:

• community hazard mapping

• storm surge and erosion monitoring

• protection of eelgrass, kelp forests, salmon systems, and blue carbon habitats

• Indigenous governance grounded in responsibilities to land and kin

• choosing ecosystem-based adaptation instead of hard shoreline defenses

This is not defensive adaptation.

This is relational adaptation.

The Haida Nation plans with the land and sea, not against them.

They are not “catching up” to IPCC recommendations.

They are already modelling them.

And this is where an important truth becomes visible:

Adaptation must protect relational integrity, not only physical assets.

In other words: resilience is not only about preventing damage.

It's much more about protecting the relationships that life depends on.

For anyone reading from outside this region, the lesson feels clear: resilience is built over generations through connection, not last-minute engineering.

2. At COP30: Indigenous presence is historic, yet protest is still necessary

COP30 in Belém is the most Indigenous-inclusive climate conference ever held, with more than 900 Indigenous participants.

And still, the Munduruku Nation staged a peaceful blockade of the Blue Zone entrance, halting access for about an hour.

Their demand was simple:

stop extractive projects threatening their territories in the Tapajós and Xingu River basins, and demarcate Indigenous lands.

The protest was called legitimate by conference leadership. Ministers met with the demonstrators. Youth spoke openly to UN News about visibility and urgency.

But visibility is not influence. Inclusion is not solidarity.

Even with a COP held in the Amazon, Indigenous peoples must still fight to be heard in systems that determine their future.

As one leader said:

“Indigenous peoples protect 82 percent of the world’s biodiversity. If you demarcate Indigenous lands, you protect the climate.”

And there is the contradiction that has always bothered me:

We still live in a world where one group decides over another group’s future.

We see it in climate negotiations.

We see it in wildlife management.

We see it in land governance.

If all humans lived with Indigenous land ethics, climate governance would look very different. But we don’t, and many of us have become placeless, disconnected from land, from food systems, from ancestry, from responsibility.

Are we homeless in the grand scheme?

Or simply untrained in the practices of belonging?

3. Why Indigenous knowledge systems strike differently

Indigenous knowledges are powerful not because they are mystical or morally superior, but because they arise from:

• relationship

• reciprocity

• obligations to place and kin

• long-term ecological memory

• feedback with ecosystems

• governance designed for collective well-being, not profit

Meanwhile, most Western governance is structured around:

• extraction

• ownership

• markets

• short political cycles

• externalized harm

• hierarchy

• technocratic distance

This is not about “good people” versus “bad people.”

It's about systems design.

Indigenous governance systems remain among the very few in the world that were not built on extraction. Their ethical lineages — the commitments that tie people to place — are unbroken.

That difference matters, especially now.

4. A circle of school kids and the blueprint of relational thinking

During a “Mobile Umweltbildung” session this week, we moved into a storytelling breakout. I shared two stories about cocoa farmers in Ghana — one treated fairly, the other exploited — and the kids shared their ideas.

Their responses were beautiful:

• empathy

• fairness

• imagination

• the desire to help

• creative problem-solving

Children are not naturally virtuous. They struggle to share, they argue, they feel jealousy.

But they are naturally relational.

They have not yet absorbed:

• hierarchy

• extractive economic logic

• scarcity narratives

• competition as identity

• the belief that knowledge = advantage

• the idea that some people matter more than others

A boy raised his hand and said:

“I would build a machine that harvests the cocoa pods and takes the seeds out so the family doesn't have to work so hard.”

A brilliant idea, and also revealing.

Children think creatively and in stories instead of silos, but they mirror the logic of the world around them.

A machine feels like the most intuitive solution because we live in a system that solves problems through engineering, scaling, and automation.

His idea was not wrong or harmful.

But it did not take into account:

• place

• culture

• ecology

• livelihood

• local context

• the plant itself

• economic realities

• long-term relationship

This is exactly why listening matters.

Innovation without relationship easily becomes extraction.

Western instinct: build, optimize, scale

Relational instinct: listen to the people, land, context, place

Both instincts are human; only one protects relational integrity.

Children must be heard before they can learn to listen, just as Indigenous communities must be heard before their knowledge can guide policy.

Children still connect feeling and reasoning.

And they understand fairness before they understand systems.

Watching them, I saw the same relational blueprint that Indigenous governance protects.

5. Knowledge should not be hoarded. It should flow like water.

In many adult spaces — corporate, academic, political — knowledge is guarded, monetized, weaponized, or turned into advantage.

Children do not naturally behave this way.

Indigenous knowledge systems do not behave this way.

And science at its core is not meant to behave this way. At least, not the science I fell in love with.

If we want resilience — ecological, cultural, or political — I think we need knowledge to circulate, not stratify. We need an education system that mirrors the (eco)systems we hope to protect.

School kids should learn:

• ecology

• ethics

• interdependence

• place

• responsibility

• story and imagination

• the sciences that explain how the world works

• the humanities that teach us how to live well within it

What they do not need is:

• political identity training

• early socialization into extractive norms

• the idea that knowledge equals advantage

• the belief that some disciplines matter more than others

Politics should not be taught as ideology.

Politics should be understood, not inherited.

Children deserve tools to interpret systems, not pressure to perform within the systems that are failing us.

It took me years to see that even adults I know and love — people who are brilliant in their hands-on worlds, like mechanics, builders, technicians — were often never given access to the humanities in ways that felt meaningful. They weren’t taught to see knowledge as relationship. They were taught to see knowledge as hierarchy.

That isn’t ignorance. It's design. It’s simply what the system taught them to value and what it taught them to ignore.

And that is exactly why education matters. What we pass on matters.

If school kids learn relational knowledge early — science, humanities, ethics, ecology — then they will understand systems without being trapped by them.

They will inherit understanding, not extraction.

They will inherit awareness, not cynicism.

And they will know that every form of knowledge, the mechanic’s hands, the botanist’s mind, the storyteller’s memory, is part of the same web.

Because if we want resilience, we need all forms of knowing at the table. And someday these kids will decide what should be protected, restored, or rebuilt.

6. Der rote Faden: resilience comes from relationship

Here is what this week taught me:

If resilience, justice, and climate repair really do depend on relationship, then it makes sense to look closely at the systems where relationship still survives.

For me, that currently looks like Indigenous governance, place-based cultures, and the ways children move through and act in the world.

Not because they are perfect, but because they remember what much of the world has forgotten.

And yes: we are running out of time. I feel this more than I used to, maybe because I spend a lot of time with kids now.

So the time we do have must be used to repair how we relate:

to each other

to land

to knowledge

to responsibilities

to the future

Resilience is about protecting these relationships that allow life to continue, and not primarily about protecting things.

And that leads to another truth: We cannot keep “buying time.” We cannot keep pushing costs into the future.

Climate delay is just another form of debt, taken out in our children’s names.

The goal must be early intervention, not late-stage crisis management.

We owe it to the next generation to act before their choices narrow.

To repair systems before they harden.

To teach relational resilience before extractive logic takes root.

Because real resilience is not technical.

It is relational.

Resilience = integrity of relationships

Reflective prompts for taking this further:

• Which relationships, human or more-than-human, have influenced your sense of resilience?

(A moment with a person, animal, landscape, or community that revealed how systems endure.)

• What knowledge traditions helped you understand belonging?

(Family teachings, craft, land-based skills, science, stories, ancestry — whatever gave you a sense of place.)

• If your community designed its future around relational integrity instead of fear or scarcity, what would shift first?

(Think local: schools, forests, rivers, housing, food, how decisions are made.)

• When in your life have you experienced “collateral freedom” — the clarity that comes after hardship?

(Moments where struggle or hardship sharpened your ability to see what truly matters.)

References

BBC News (2025). Brazil creates new Indigenous territories during protest-hit COP30.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c1d0vekq12ro.amp

UN News (2025). Indigenous protesters block COP30 entrance, demand action from Brazilian Government.

https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/11/1166373

Council of the Haida Nation & Province of British Columbia (2015). Haida Gwaii Marine Plan.

https://coastalfirstnations.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Haida-Gwaii-Marine-Plan.pdf

Natural Resources Canada (2025). Coastal Flood Hazard Assessment for Risk-Based Analysis on Canada’s Marine Coasts.

https://natural-resources.canada.ca/coastal-flood-hazard-assessment-risk-based-analysis-canada-s-marine-coasts

IPCC (2019). Summary for Policymakers: Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate.

https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/summary-for-policymakers/